Ken Kirkby

Ken Kirkby

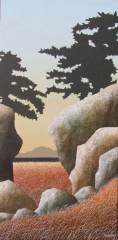

Canadian 1940 – 2023

by Mark Hume

Canadian landscape painter, fly fishing master, skilled wing shot, epic storyteller and environmental champion, Ken Kirkby, has died at his home on Vancouver Island. He was 82 and was active in his studio until a few weeks before his death, from cancer. Kenneth Michael Kirkby was born on September 1, 1940, in the middle of an air raid on London, England during World War II. He often claimed the dramatic circumstances of his birth and his family lineage – which can be traced back to the Viking leader Rurik – made him the warrior painter that he became, unleashing his creativity with a fierceness, passion and stamina that was remarkable…

KEN KIRKBY

Canadian 1940 – 2023

by Mark Hume

Canadian landscape painter, fly fishing master, skilled wing shot, epic storyteller and environmental champion, Ken Kirkby, has died at his home on Vancouver Island. He was 82 and was active in his studio until a few weeks before his death, from cancer. Kenneth Michael Kirkby was born on September 1, 1940, in the middle of an air raid on London, England during World War II. He often claimed the dramatic circumstances of his birth and his family lineage – which can be traced back to the Viking leader Rurik – made him the warrior painter that he became, unleashing his creativity with a fierceness, passion and stamina that was remarkable.

He painted his whole life, often daily for long hours, and died peacefully on June 20, 2023 with his wife, artist Nana Cook, and his son Michael, who had flown in from his home in Japan, at his bedside.

Ken spent his early childhood in Portugal, where he began drawing, and painting, and where, at age 16, he held his first art show in Lisbon. Portugal at that time was experiencing political upheaval under an authoritarian regime, so Ken, on his 18th birthday, brought his family to the safety of Canada, arriving in British Columbia in 1958, where he fell in love with the outdoors and all of the possibilities it presented to someone with a rod, gun and paint brush in hand.

One of his first fly fishing trips was for sea-run cutthroat off the beaches at Nile Creek, near the small community of Bowser, on Vancouver Island, an experience he said imprinted both the beautiful fish and the rugged West Coast landscape on him. He promised himself he’d move there one day, but he had a lot of living to do before that dream came true.

For five years in the 1960’s, drawn by the wild landscape of the North, Ken travelled widely in the Arctic. He was then just a young, emerging artist looking for inspiration and perhaps more importantly, for himself. He found both.

The story he tells is that one day walking alone across the barrens he saw another person in the distance, but when he drew close found it was just a pile of rocks. They weren’t lying in a natural state but had been stacked in the shape of a human figure, an Inuit signpost known as an inuksuk. It was brooding, Shamanistic and somehow comforting. It cast a spell on him.

Inuksuit, which is the plural for inuksuk, can be found all across the Arctic, from Alaska to Greenland. Some are built with small windows, framed spaces which,

when you look through them, reveal a good hunting or fishing spot. In some places they run out across the landscape like markers on a trail. In the blowing snow, when everything is the same, they are the signposts home.

When Ken left the Arctic the images of those stone figures stayed with him long after. Returning to Vancouver, he married Helen Michalchuk and had his only child, Michael, a son he adored, admired and whom he would later take to the Arctic and teach the craft of fly fishing.

For many years Ken concentrated on painting Arctic scenes, finding commercial success when the Alex Fraser Gallery began selling his landscapes, which captured the vast wildness of Canada, as fast as he could produce them. But his paintings of inuksuit weren’t popular at first. The silent, brooding stone figures didn’t seem to connect with the public. Ken persisted in painting them, however, because he felt they were awe inspiring, and eventually he had a breakthrough and his paintings of inuksuit became popular. In 1992 he unveiled his massive Arctic painting, Isumataq, in Parliament, contributing to the growing awareness in the nation about the importance of the Arctic and helping to establish the inuksuk as a national symbol which would later be featured on coins and postage stamps.

In 1993, Ken was awarded the Commemorative Medal for the 125th Anniversary of Canadian Confederation by his dear friend and longtime fishing partner, the Honourable John Fraser, then Speaker of the House.

Isumataq, an oil on canvas painting nearly four metres high and 46 m long, took Ken 12 years to complete. Its massive scale was too much for private galleries to handle, but it was exhibited at Art Expo, in New York, the Museum of Nature, in Ottawa, and for a year at Ontario Place. During the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics, which adopted the inuksuk as its logo, the painting was shown at an ice rink, a venue which Ken said in Canada was like being displayed in a church. “Only it’s better,” he said at the time. “More people go to hockey rinks.”

When he was 61, Ken finally realized his dream of living near Nile Creek, giving up his residence and studio in downtown Vancouver to occupy a small cottage on a beach near the estuary. His studio was an adjacent red barn, which he reluctantly shared with a family of otters.

Living on Vancouver Island he shifted his focus from the Arctic to West Coast landscapes, but as he wandered the waterfront near his home he wondered where all the fly fishers had gone. He soon learned that the sea-run cutthroat and pink salmon fishing which had made the area famous when he was a young man had declined drastically. His response was to throw himself into the Nile Creek Enhancement Society, helping to restore stream habitat, planting eel grass beds, and rearing tiny pink salmon fry in the organization’s small hatchery.

He prompted the society to do stream improvement work without waiting to get authorization from slow moving government agencies, arguing that it was unlikely they’d be fined for improving the environment. He was right. The salmon and sea- trout populations soon rebounded, with massive runs of pinks returning to spawn in Nile Creek.

Perhaps his biggest contribution to environmental causes were the fund raising art auctions he organized, featuring many of his own paintings, and the works of other artists who he recruited to the cause. At one event he finally met Nana Cook, a painter whose work he had long admired. She was, he told a close friend, the love of his life and they were married in 2017, wearing chest waders, and standing in the waters of Tunkwa Lake. After exchanging vows they drank a glass of champagne, and then went fly fishing together. It was a short honeymoon, he said later, but the trout were very big.

After the wedding Ken gave up his waterfront cottage, said goodbye to the otters, and moved in with Nana, whose iconic Canadian log house looks out on the Salish Sea. It was, he said, the start of the happiest time of his life.

Together they roamed the landscapes they loved to paint, looking for inspiration, and often finding it, and joy, in each other.

“He had a wonderfully witty and wicked sense of humour, and believed that to stay healthy one needed three good belly laughs a day,” said Nana. “He was compassionate, loving, generous, comfortable being emotional, was as excited about painting at 82 as he had ever been, and we kept no secrets from each other. He was passionate about fishing and bird hunting, from childhood to the day he died. We got married and became true life partners in everything we did. I loved him with every part of my soul.”

She was not so passionate about his homemade wine, which he said was concocted using a secret Portuguese recipe, but many of his friends willingly stepped up to help him drink it and to listen to his tall tales about life.

Only weeks before he died Ken was still laughing with his friends, and working daily in his studio. He was excited about trying a new technique on two paintings he had on the easel and was busy filling orders for galleries.

In one of his final acts Ken donated 50 paintings to the Comox Valley Project Watershed Society for future fundraisers.